As the race to vaccinate populations against COVID-19 gathers pace, the gulf between the haves and have-nots has grown ever starker. Vaccine inequality has exposed global disparities in the same way that the pandemic has laid bare social divisions from the start.

While wealthy nations have hoarded enough vaccine supplies to inoculate their populations sometimes more than twice over, low- and low-to-middle-income countries have been left with unequal access. This means that the vast majority of these populations—including people in crisis-affected regions—will not have access to the COVID-19 vaccine for years, let alone in 2021. As Mesfin Teklu Tessema, senior director of health at the International Rescue Committee (IRC) says, “This is an unacceptable outcome.”

It takes everyone to end a pandemic

Ending the pandemic can only be achieved if vaccines are available in all countries – to all populations, including refugees and displaced people fleeing conflict and other crises.

COVAX, a global initiative hosted by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, was set up to address this urgent need. However, COVAX has estimated the COVID-19 vaccine will reach only around 20% of populations across low- and lower-middle-income countries in 2021.

Reaching people in crisis-ridden regions is particularly important. Places like Syria and Yemen that are experiencing conflict have weak health systems and less capacity to directly respond to COVID-19. Couple that with cramped spaces—like those in refugee and displacement camps—and you end up with the potential for high transmission rates and ripe conditions for new and deadly variants to develop.

“Yet", says Heather Teixeira, health policy and communications advisor at the IRC, “some 60% of countries that are getting their vaccines through COVAX have not included refugees or internally displaced people in their national plans, which may mean that they will lack access to COVID-19 vaccines. We can’t end this pandemic unless there’s widespread global vaccination that includes these populations.”

The IRC is urging high-income countries to increase their investments to both COVAX and broader humanitarian assistance that remains every bit as essential and lifesaving, especially given the severity of COVID-19’s secondary effects.

COVID-19 disrupting essential health care

As already struggling health services prioritise COVID-19, other essential health services like routine immunisations have been suspended or delayed. Disrupting immunisation services, especially for children, poses far greater risks for young lives than the coronavirus itself.

We saw this during the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where measles deaths were actually triple the number of deaths from Ebola.

Strong and inclusive health systems are essential in providing lifesaving services to the last mile – including COVID-19 vaccines.

In Bangladesh, the risk of this pattern repeating itself is ever present. Even before the pandemic, a weak health system and shortages of qualified health workers meant that the more than 870,000 Rohingya living in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar received little care. COVID-19 has intensified these vulnerabilities, disrupting other services like routine measles and rubella vaccines for children. “Strong and inclusive health systems are essential in providing lifesaving services to the last mile – including COVID-19 vaccines,” says Mesfin Teklu Tessema. “We can’t end this pandemic unless we invest in strong health systems that deliver better health for all of us.”

Leveraging IRC expertise to deliver vital care

The prognosis isn’t all negative, though. With the IRC’s strong track record in responding to health emergencies and extensive networks in the 40 countries where we work, we are making sure people displaced by conflict, climate change and other crises are included in the vaccine rollout and are ready to receive it.

A crucial part of that is sustaining and enabling routine health care, and we have this experience with routine immunisations. In Ethiopia, we tapped into our family planning programmes to immunise children who currently fall outside mainstream services. In 2019 alone, our health services reached tens of millions of people worldwide. The IRC is therefore uniquely well-positioned to expand access to immunisation in a situation where COVID-19 has derailed existing programmes.

We have also piloted innovative ways to keep track of the health records of people who may be escaping war or other crises and are therefore on the move. The IRC is the primary health care provider along the Thailand/Myanmar border. We developed a Digital Health ID which collects all of a patient’s health records into one digital file that moves with them as they cross borders. This helps to avoid duplication of treatment and ultimately benefits the health of people seeking refuge.

The key to successful delivery of these services is effective health care staff. We have substantial experience in strengthening the capacity of front-line health workers to vaccinate populations in some of the most extreme and volatile places on earth.

“When COVID-19 hit, we had been training people for years in contact tracing and how to use personal protective equipment (PPE) during our Ebola response efforts,” says Heather Teixeira. “We have been able to use that expertise in this response.”

Bringing the COVID-19 vaccine to crisis hotspots

Right now, the IRC is working with partners and funders to figure out how to support the COVID-19 vaccine rollout in the many countries where we work. This includes advocating for the inclusion of refugees and displaced persons in national vaccination plans.

We are also helping countries prepare for the COVID-19 vaccine rollout by setting up isolation units, procuring PPE all the while ensuring that clinics and hospitals have access to essential supplies like medical oxygen, testing kits for COVID-19, and to clean water and sanitation. As the vaccines become available, we will administer them as we’re able through the network of health facilities we currently support.

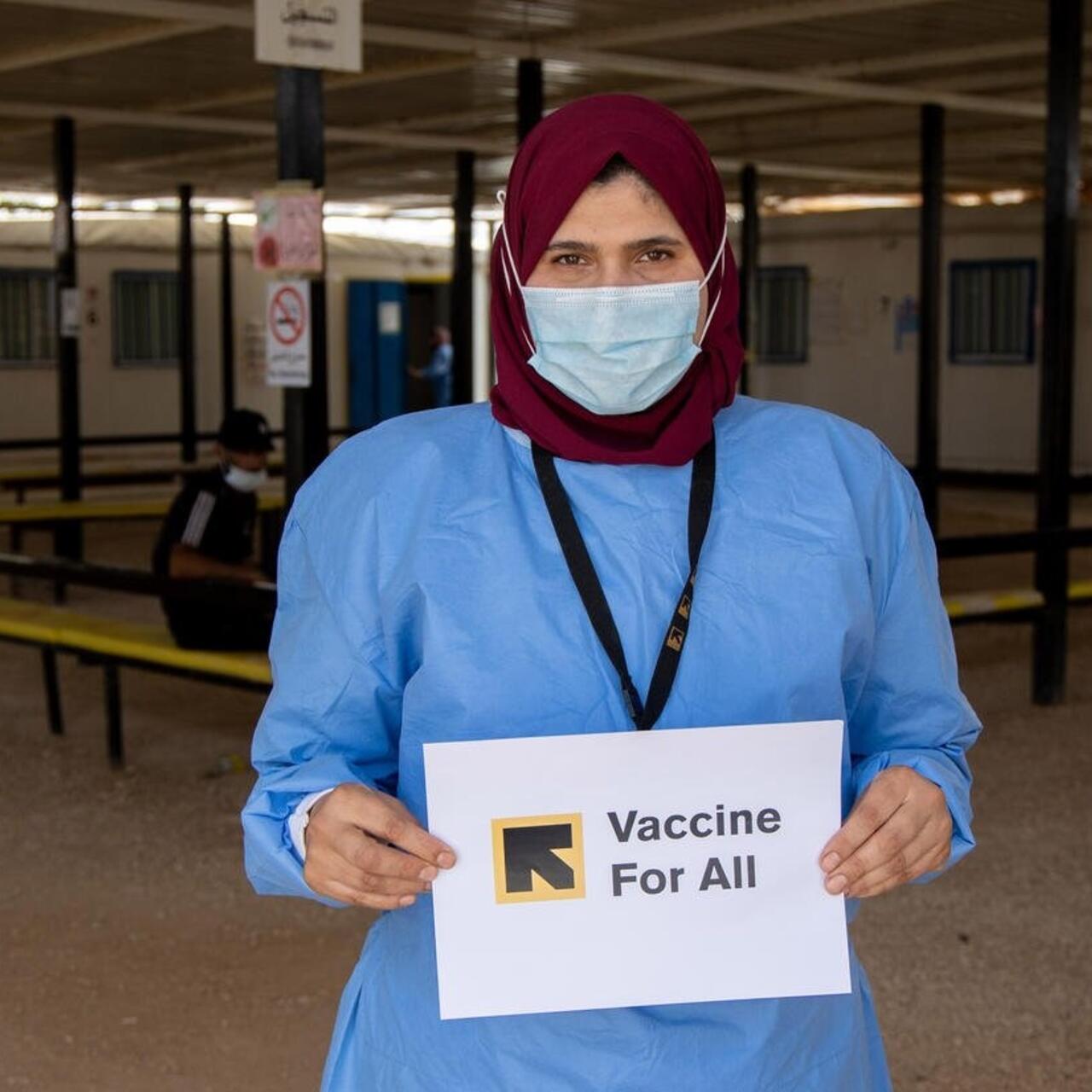

One of these is the clinic we run in Zaatari refugee camp in northern Jordan. The ministry of health has designated it a COVID-19 vaccination site, and many IRC health workers there have been trained by the ministry to administer the vaccine. The vaccination campaign started in mid-April 2021 and will eventually cover the approximately 80,000 Syrians who live in Zaatari.

Jordan was one of the first countries to offer the vaccine to refugees – in fact, including refugees in the vaccine rollout was part of the country’s plans from the very beginning.

In Uganda, the story is similar. Ministry of health staff there are vaccinating health workers through the clinics we run in Bidi Bidi refugee camp in the north, home to some 270,000 South Sudanese. With IRC health workers trained to administer the vaccine, priority groups living in Bidi Bidi, such as the elderly, will soon receive their jabs.

To prepare communities in Uganda for the vaccine, we gave health education talks at centers for the elderly and are currently participating in radio talk shows to spread accurate information more widely and answer any questions from listeners. We have also engaged motorcycle taxis equipped with loudspeakers to act as mobile messengers.

International action urgently needed

As the world rushes to distribute COVID-19 vaccines globally, it can’t forget the millions of children who still need routine health care and immunisations. The international community must devise targeted strategies to make sure the most vulnerable children in crisis-affected countries are not left behind.

To do this, we need investment in initiatives that strengthen community health workers and health systems in these contexts. The IRC trains these health workers who are an essential—and sometimes the only—link between communities and health systems. Without them, many would have no access to health care at all.

For community health workers to be effective, a functioning health system is essential. In countries blighted by conflict, natural disasters and mass displacement, health systems are weak. With enough resources, we can continue to strengthen them. We also need more innovations—such as efficient cooling technology to preserve vaccines—that speak directly to the needs of the hospitals and clinics in these contexts.

Everyone deserves equitable access and everyone has a right to health.

Finally, people will only want vaccines if they trust them and the local health services administering them. From mobile information units, to education drives, to radio shows, we are working with health workers, religious leaders, and other trusted spokespeople to share accurate information about COVID-19 vaccines.

In the end, a positive solution to the coronavirus crisis can only be achieved when everyone—including people in the hardest-to-reach parts of the world—is accounted for in the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. “Everyone deserves equitable access and everyone has a right to health,” says Heather Teixeira. “We cannot end the pandemic until all populations have access.”