T is for "Thanks"

An English class is much more than an education for refugee children in Serbia. It’s a lifeline.

An English class is much more than an education for refugee children in Serbia. It’s a lifeline.

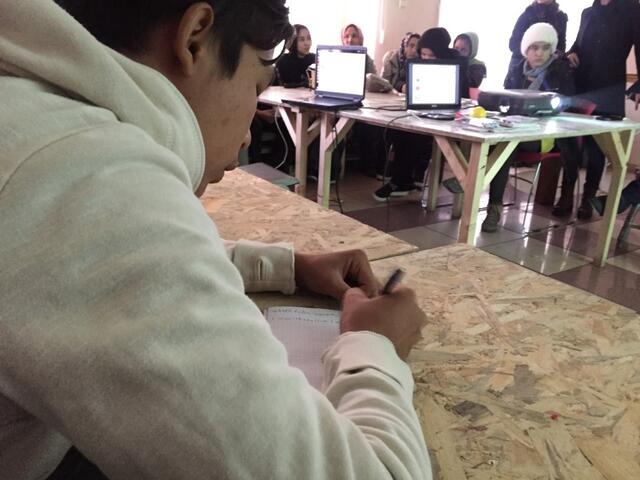

It is a cold winter afternoon in Belgrade. Inside a tiny, single-story building the size of one small room a group of children are gathered and they are learning English. This is an animated group: a mixture of girls and boys, bunched up together at tables with hardly enough chairs and benches to go around.

“There used to be more room,” says Edin Sinanović, the young founder of Refugees Foundation, the small volunteer organization in Serbia that runs this space, “but then the girls started to come.” As if on cue the door from the street opens and, alongside a cold blast of winter air, a group of about six young girls push gently in, full of apologies for being late. Somehow, like magic, more space is found and they settle right in.

The class starts with these students throwing a ball from one to another. The throwers have to introduce themselves, and describe what they like to do. They are reminded to talk in full sentences: “My name is …,” “I am from …,” “I like to…” It’s all very revealing. They like friendship. One likes to play the piano.

The teacher, Isidora, corrects them on pronunciation — it’s “like” not “like-es,” she guides them. One of the boys says he likes sleeping, and then throws the ball, at high speed, to me. I catch it and everyone is impressed (myself included). I said I liked dancing, which got widespread approval from the room. I threw the ball to one of the girls and she, from Afghanistan, liked studying.

As the game continues the questions become more forward-looking. “What would you like to be?” the teacher asks. “I would like to be a doctor,” one girl answered. “I would like to be a teacher of mathematics,” said another.

Where do you want to live in the future? “I would like to live in a beautiful country,” one said. Another said France. One more said London.

These kids are all refugees — about twelve girls and eight boys. All of the boys are travelling alone — without their families — and are staying at an asylum center outside of Belgrade that has special accommodation for children like them. By and large they have come from Afghanistan and they have endured much hardship on their trek to Belgrade.

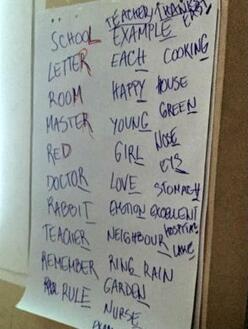

The class progresses with a word game: You need to call out a word that starts with the last letter of the word that came before. It’s fun and the students go around the room at least three times with this game. Isidora writes each word up on the whiteboard, underlines the last letter and on they go.

It gets competitive.

There is a pretty wide selection of vocabulary in the class so the students all have different ideas about what word should come next. One such moment was the word to follow “doctor.” A word beginning with “R.” One of the young Afghan boys had an idea of what that word should be. He was, it’s true, the most confident and outgoing in this group, a guy who is clearly smart and had already boasted proudly that he can speak some German too.

Challenging him was a young Afghan girl, wearing a snug pink jacket and a knitted cap. She was small where he was tall. She was quiet where he was loud. But she was determined to be heard. “Rabbit” she cried out, her arms outstretched, determined to be seen as well. “Rabbit!” And “rabbit” made it to the whiteboard. She was very pleased.

The teacher is a psychologist and it is her job, in addition to teaching English, to keep alert for any refugee kids who may be in need of help overcoming trauma they have experienced.

This English class is run by PIN, one of the local humanitarian organizations the International Rescue Committee supports in Serbia. Although it is a straightforward English class it is also the very beginning of what’s called a psychosocial intervention. The teacher is a psychologist and it is her job, in addition to teaching English, to keep alert for any refugee kids who may be in need of help overcoming trauma they have experienced.

“When we started these lessons, with the aim to reach the most vulnerable kids, particularly those hundreds travelling by themselves, alone, we knew that most children who would walk through our door to learn English would need some sort of psychosocial support,” says Natasa Simic, who manages PIN’s project targeting vulnerable children. PIN stands for Psychosocial Innovation Network, an apt name for an organization doing pioneering work to meet the specific psychological needs of asylum seekers in Serbia.

No matter their cheery disposition today, these kids have, for the most part, fled war. They have all, whether traveling by themselves or with their families, endured a grueling odyssey from Afghanistan to here, travelling across Iran, Turkey, and Bulgaria.

There are now over 6,900 refugees in Serbia — they are stalled here, with limited options for onward movement. It is critical that they have opportunities to stimulate their minds, to learn, to expand their knowledge. This tiny little ramshackle oasis, in a dilapidated building right next to an “erotic shop” on a run-down street in Belgrade, does what it can to do just that.

In the classroom, the word “each” led to “happy,” (although one of the kids yelled out “Hungary!” which got a laugh), led to “young,” led to “girl,” led to “love,” led to “emotion.” The students all laughed.

The last word, coming from the word “East,” was “Thanks.”

This piece was first published on Dec 21, 2016 in Uprooted, an International Rescue Committee publication on Medium that focuses on the refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East.