In November 2020, the internet and phone lines were cut off in Tigray, northern Ethiopia, amid rising tensions. Violence escalated, while the rest of the world was left in the dark about what was happening.

Mulu, Berhan and Azmera are three women who fled Ethiopia to seek refuge in Sudan. Their stories are crucial in enabling the world to bear witness to the horrors that continue to unfold today.

Mulu

“We were thankful with what we had,” says Mulu, reflecting on her life in Tigray before she escaped to Sudan. Mulu’s family led a comfortable, happy life, renting a home in the town of Humera. Her husband used to trade goods with Sudan.

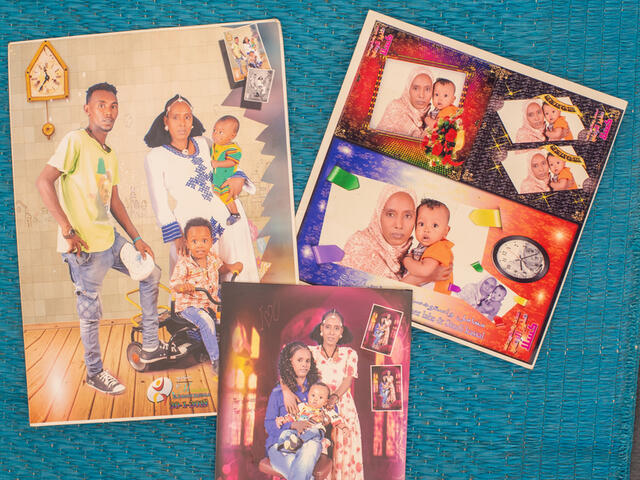

“I was baking injera [flatbread] when the war began,” Mulu remembers. She went from making lunch for her two children to scooping them up to run for their lives as their neighborhood came under attack. She was able to grab only a few possessions. “The photos were hanging on the back of the door when we left,” she says, cradling the pictures that remind her of the life she left behind.

When we left, a bomb exploded under the date tree where we had just been standing.

“When we left, a bomb exploded under the date tree where we had just been standing,” she says. “During the journey, there was a pregnant woman with her husband. The husband died on the way. We buried him and continued on.”

Using a jerrycan as a boat to cross the river to Sudan, Mulu and her family arrived at Tunaydbah camp—along with 60,000 other refugees . “My baby girl didn’t even have clothes,” she explains. A friend living in Sudan was able to get together some money and baby clothes.

Mulu constantly thinks about the rest of her family, now scattered. “Living without knowing the whereabouts of your family [makes you] live in constant worry,” she says. “I don’t know where my mother and sisters are. As for my brother, I heard about his death from the television.”

As a result of chronic stress, Mulu’s health has deteriorated. “From the day the war broke out, I was constantly getting sick,” she explains. Mulu has been able to get treatment at an IRC-run health center at the border of Ethiopia and Sudan, which has helped.

Despite these harrowing experiences, Mulu holds on to hope. “Will this time pass? May we go back to our homeland from this desert?” she asks, a solemn look on her face. “After all this loss, the hope that we may see our homeland again sustains me.”

She wishes for peace to prevail, so her children can have a future. “I want [my children] to return to their homeland so that they get educated, and for the war to stop so that we can meet our family once again.”

Berhan

“My village was peaceful. I had a great hotel, and a huge house,” says 60-year-old Berhan, reminiscing about her life before the war.

With the coming of conflict, her hotel was looted and her property seized. When Berhan returned to gather a few last possessions, she was captured and put into prison for two months, separated from her family.

Now with nothing to her name except the prison garb she was issued, and knowing that her life would always be in danger, Berhan resolved to escape Ethiopia the minute she was released from captivity. “Even if I died on the way, it was better than being killed,” she explains.

Even if I died on the way, it was better than being killed.

Beginning her journey at 3am, she wandered into the barren outskirts of her hometown, waking through thickets of thorns that tore at her skin. He feet blistered and she developed severe leg cramps. She encountered a young boy who told her she was walking in the wrong direction. He began guiding her to the border with Sudan.

“I was carried over the river,” she says, describing the moment she crossed to Sudan. “My legs just couldn’t walk anymore.”

Once in Sudan, Berhan was reunited with her daughter in Gedaref refugee camp, where she received treatment for her legs at the IRC’s health center. “I am relieved that we have somewhere to sleep at night,” she explains. “But we can’t sleep. Our minds can’t deal with the things we’ve experienced. Even if we try to forget them, we can’t get rid of the memories.”

Like Mulu, Berhan remains hopeful that she will return to Ethiopia and reunite with her two sons. “I have never seen anything like this in my lifetime,” she says wistfully, looking into the distance. “I worry about my children.”

She dreams of peace, so other families like hers can once again live like they used to. “If we can’t achieve peace, we can’t do anything,” she says.

Azmera

“We had a decent livelihood back home,” says 30-year-old Azmera*. “We had freedom and lived a good life.”

Azmera earned a decent wage working for a company in her hometown of Humera. But when violence erupted, the company’s offices were looted and Azmera couldn’t access her bank account.

She and her family hid in the wilderness surrounding Humera, hoping the violence would subside. But when they returned to town, Azmera saw the casualties firsthand—young people who felt they had no reason to flee had been slaughtered. “They were only civilians,” she said. “Peaceful young adults who were unarmed.”

Azmera has a disabled leg and struggles to walk for long distances, but she now had no choice but to journey to safety. She set off with her daughter for Sudan, hiding and sleeping in the rough for two days. They were pursued by soldiers seeking to capture anyone on the run. Azmera saw pregnant women laboring to continue on, no medical services available. Some never made it to the border.

Our children had better lives before, when there was peace.

After crossing into Sudan, Azmera managed to put herself and her daughter out of immediate risk. Now living in Tunaydbah camp in eastern Sudan, she ruminates over all she left behind. “Our children had better lives before, when there was peace."

“My daughter used to go to preschool,” she says, but now she suffers from anxiety and depression.

Azmera has seen improvements in her daughter’s mental health since she started bringing her to classes at the IRC-run safe space for chidlren. “When she comes home, all she does is talk about school,” she says, smiling at her daughter. “It has really helped to lift the depression.”

Azmera envisions Tigray peaceful again, the violence nothing but a bad memory. She imagines her daughter getting the education that will be her lifeline to a better life. “I hope she becomes a career woman who helps the Tigrayan community,” says Azmera, looking lovingly at her daughter. “Not only the Tigrayan community, but the world as whole.”

The IRC's health centers and safe spaces for children in Sudan are supported by funds from the European Union. A version of this story was first published by IRC EU.