What is malnutrition and how can we stop child hunger?

The IRC spoke with malnutrition expert Dr. Mohamed Kassim about how the IRC is protecting milestones in Nigeria through malnutrition prevention and treatment.

The IRC spoke with malnutrition expert Dr. Mohamed Kassim about how the IRC is protecting milestones in Nigeria through malnutrition prevention and treatment.

For parents, seeing their child’s first smile, watching their initial wobbly steps, and hearing their child begin to form words are all precious milestones as they grow up. But for children living in countries facing some of the worst crises in the world—like Nigeria, Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen—precious moments are put at risk because children don’t have access to one of life’s basic necessities: nutritious food.

Fifty million children worldwide suffer from acute malnutrition every year. Even though treatment is available, accessing it is challenging. Lack of access to treatment is caused by a number of factors. In northeast Nigeria, drought and conflict have created massive food shortages, making it hard for parents to provide nutritious food to their toddlers.

Dr. Mohamed Kassim has been contributing to the International Rescue Committee’s malnutrition response in Nigeria since 2016, supporting thousands of families. We spoke with him about the causes of malnutrition, the challenging contexts of conflict and climate, and how the IRC is finding sustainable ways to end child hunger in northeast Nigeria.

Last year, thanks to the support of people like you, the IRC treated 161,000 children under 5 worldwide for severe acute malnutrition. In Nigeria alone, the IRC treated 32,000 children under 5.

Malnutrition is caused by a lack of nutrients, either as a result of a poor diet or problems absorbing nutrients from food. It isn’t just hunger. It’s a life-threatening condition that can rob children of the opportunity to live full and healthy lives

In northeast Nigeria, the IRC works with mothers and their young children who have been identified as undernourished. “When we are looking for malnutrition in children, we start from when the mother is pregnant, to the time the child is delivered, and all the way to when a child reaches up to 5 years old,” Dr. Kassim explains.

“If a mother is malnourished herself and underweight when she delivers her baby, this may lead to her child becoming malnourished,” says Dr. Kassim. “That is the first component of what causes malnutrition in a child.”

Dr. Kassim describes how malnutrition causes fat and muscle tissue to waste away. His team is able to make quick analysis based on the height and weight of a child.

Other symptoms include changes to skin and hair. “Dermatosis is where the skin starts peeling off,” explains Dr. Kassim. “Hairs become very brittle and might change color.”

“Children with malnutrition are more vulnerable to infections and illnesses because their immune system becomes low,” adds Dr. Kassim. If malnutrition is not treated quickly, it may impair a child’s ability to learn for the rest of their lives.

In northeast Nigeria, drought and conflict have created massive food shortages. When people become displaced, parents struggle to provide food because “they no longer have a consistent supply,” Dr. Kassim says. “When livelihoods are depleted, there is food insecurity.”

“There are also cultural practices that may hinder what a child is fed,” Dr. Kassim says “Some mothers believe that breast milk is not adequate for the baby’s growth and that they must feed their babies other traditional foods. Some believe that colostrum, the first milk produced after mothers deliver, is not good for the baby and they must discard it and not give it to the baby. In fact, this milk is nutritious and good for the newborn.

“Some mothers encounter unplanned pregnancy while breastfeeding very young infants. Some believe that the breast milk of expectant mothers is not good for the child. There is a general perception that it causes diarrhea. Many mothers take the advice and terminate lactation prematurely.

“At the IRC in Nigeria, it's recommended that children are exclusively breastfed for six months after delivery,” Dr. Kassim explains. “When this is not practiced, it can contribute to the development of malnutrition later in life or as the child grows.”

“The other cause of malnutrition is common illnesses that could be prevented through immunization,” says Dr. Kassim. “If that doesn't happen and the child gets sick, feeding becomes a challenge, then that gravitates into malnutrition.”

If a baby doesn’t receive its vaccinations for preventable illnesses, the risk of them becoming sick is higher. This can contribute to many risks to the baby's health. Children who have not received all their vaccinations have a higher chance of suffering from malnutrition

The IRC is working to both prevent and treat malnutrition in children. Here are some of the ways our teams are doing this important work in Nigeria:

The IRC currently runs five inpatient stabilization centers in Nigeria for more severe cases “These are for quite sick children,” Dr. Kassim explains. “We admit mothers and children for at least one week. Then we transition them to the outpatient program for another six to 12 weeks.”

All five centers combined can accommodate 160 children. “Children with severe acute malnutrition with medical complications come with various underlying issues,” says Dr. Kassim. “They can be treated for hypoglycemia (low blood sugar levels), shock, serious infection, worms, malaria, skin ulcers, measles, ear infections, meningitis, anemia, tuberculosis, low body temperature, micronutrient deficiencies, dehydration, persistent diarrhea and eye infections.”

The outpatient program is for children who come for treatment for the day but go home. For less severe cases, the IRC runs a “targeted supplementary feeding program” where children are offered ready-to-use supplementary food and mothers are counseled on best feeding practices. “The IRC monitors a child’s progress until they are fully recovered,” explains Dr. Kassim..

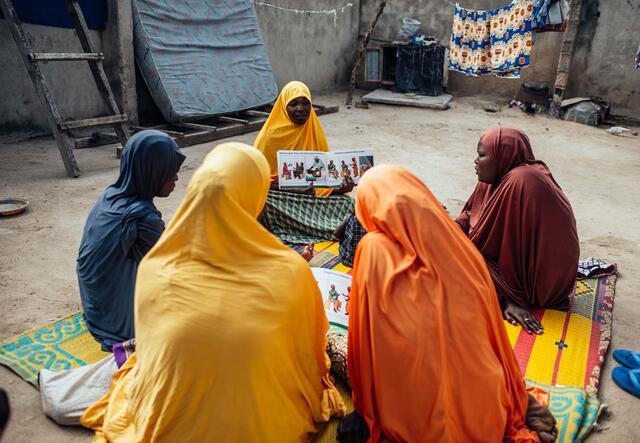

The IRC also works closely with local communities and leaders to strengthen health systems that prevent malnutrition in young children. “We've empowered groups of mothers in the various communities we support,” says Dr. Kassim, “They are given training on how to use the MUAC tape [for mid-upper arm circumference measurement] used for assessing malnutrition in children and refer cases for further evaluation.” By empowering women, the IRC is able to reach more mothers and babies. “For those who are not educated to read, we've given them color-coded tape—a certain color means malnutrition.”

Mentoring community groups involves training, coaching and guidance on the best nutrition practices so that the members can learn and start influencing the attitudes of other community members.

“It made a lot of difference because children are now getting referred on time, which will bring a better outcome in terms of the treatment,” says Dr. Kassim. “If the referral is delayed, it will take longer to treat the child and use more resources and time. The faster the child gets treated, the less complications.”

The IRC is also working with fathers. “They have a lot of influence on the family’s decision making,” explains Dr. Kassim, “so we are trying to see how we can get them involved through the mentoring communication groups that we have.

“By bringing men on board through the men-to-men committees, there was great change and more women are able to take their children to the stabilization center for treatment and care.”

Through strengthening community systems, the IRC aims for nutrition work to be run solely at a community or state level in the future.