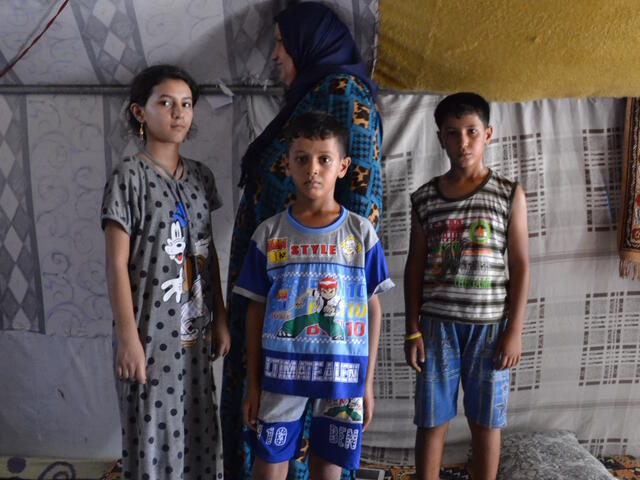

“ISIS killed my husband,” Abeer* says as she sits in her sweltering tent in a windswept camp in the suburbs of Baghdad. Her three children, ages 9, 10 and 13, keep close to her as she describes the trauma they experienced over the past three years.

“It was a very hard life,” Abeer continues, recalling the more than two years she spent living under ISIS control after the militant group took al-Qaim, a town of 150,000 on the Euphrates River in southwest Iraq, in 2014.

ISIS imprisoned Abeer’s husband and imposed their harsh rule on residents of the town. Business owners and farmers were extorted, livelihoods destroyed, classrooms co-opted. “My children weren’t going to school—now they are behind in their education,” says Abeer. ISIS cut off contact with the outside world. Food and medicine became scarce. Men were brutally punished for perceived transgressions, women and girls—coerced into covering even their eyes—avoided going outside.

Across Iraq more than 5.5 million people have been forced to flee their homes not only by the horrors of ISIS but by fighting to retake control of ISIS-held areas. Today only al-Qaim remains in their grip.

When after two years of no news Abeer learned that her husband had been killed in captivity, she knew she had to flee. She and her brothers paid smugglers 1 million Iraqi dinar ($850) to help them escape to this camp outside Baghdad. “I managed to save my life—and my children’s lives,” she says. “But I left everything I own behind.”

Life hasn’t been easy in the camp. “I spend all my time here,” Abeer says. “I don’t often leave my tent.” There are few common areas where people can socialize, and the heat is oppressive. When people had a problem, they had no one to turn to for help—until now.

Creating change

To reach people like Abeer, the International Rescue Committee is training and supporting residents of the camp to amplify the voices of their neighbors, and empowering them to be able to fix the issues the community is facing themselves.

The IRC establishes Community Representation Groups that work to promote understanding of ongoing problems and develop plans with camp authorities to improve daily life. Mariam, who fled Mosul at the start of this year, has trained as a community representative and now spends much of her day listening to the challenges and concerns of her fellow residents.

“Instead of talking through Facebook, we have our own approach—it’s called talking face-to-face!” Miriam jokes. “Every day I walk around the camp and check in on how everyone is doing. People have someone to go to, to help them fix their issues and get what they need.”

“We talk to Mariam about everything,” says Abeer. “I tell her about my personal issues and whatever is worrying me that day.”

Life is getting better since the creation of the Community Representation Groups. The health care facilities have adopted regular hours, and trash collection has improved. “Now the camp management is far more active and everything is much more organized,” says Mohammed, another community representative. “I decided to join the group because I wanted to serve my community, to serve my family and my friends. I am living here and struggling—I understand the needs of people, and so I want to help relieve their difficulties.”

Having women in the group is crucial, adds Mariam, as many only feel comfortable talking with other women. “Two days a week I have meetings with women to listen to what they need, hear how they are feeling, and what is proving a struggle. I then pass that information onto aid organizations like the IRC, who can help them.” Often people lose essential documents, which means they can’t access services—and for divorced or widowed women, this can be a very personal issue. “Now these women have a place to go where they can talk in private.”

An uncertain future

The residents’ future is far from clear. Nearby camps have closed, and rumors are rife that this one will shut down as well. Many families from eastern Anbar and other areas retaken from ISIS have returned before they felt ready due to this uncertainty. Today, those left in the camp are mostly from Mosul and from areas in western Anbar that are still under ISIS control.

“I think about this all of the time,” says Abeer. “I have no place to go. I can’t go home, because ISIS is still in control, and I don’t have money to pay rent in Baghdad. And I don’t want to go to another camp … the services aren’t as good, the school is too far away. And the same with the clinic and the hospital.”

Both Mariam and Mohammed worry that these rumors and the camp closure will mean people are forced into a future that they would not choose. It’s likely that some people will go back to their homes before they feel it is safe, while others will have to start their lives over again in another camp or town. They spend time making sure residents have the latest news on the camp and continue to advocate on their behalf.

“The Community Representation Group is here to try and solve this problem, to keep the camp open and support people through this difficult time,” Mohammed explains. “So far we have managed to postpone this decision.”

*Name changed to protect her privacy