As thousands finally escape from Boko Haram terror, a food crisis lingers

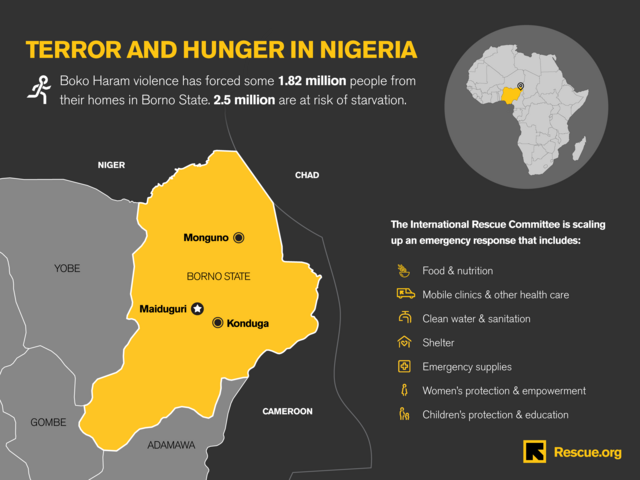

Without urgent aid, a food crisis may leave up to 2.5 million people at risk of starvation in northeastern Nigeria.

Without urgent aid, a food crisis may leave up to 2.5 million people at risk of starvation in northeastern Nigeria.

Tears stream down Hawa’s face as she recalls her brother’s death. He was shot in front of them, in front of her and her family. Her youngest daughter, as if by instinct, gently touches her knee. She’s seen her mother in this state before.

Maiduguri, one of the largest cities in northeastern Nigeria, overflows with stories of indiscriminate death and devastation. An estimated 1.4 million people living in the more than 30 official and unofficial camps speak of homes set ablaze, of husbands and brothers shot in front of their wives, sisters and children, of relentless violence against women and girls, of families fleeing on foot for days with little food or water, with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

The militant group Boko Haram has ravaged this part of the country for years, and while they’ve begun to lose ground to government forces, the terror they’ve inflicted maintains a firm hold on the psyche of millions. With no means of income and their once prosperous farms and businesses scorched, people here struggle to scrape together enough food for themselves, let alone their families.

Falmata Usman, a 28-year-old mother of four, has brought her six-month-old daughter to an International Rescue Committee clinic.

“My baby is sick because of a lack of enough food,” she tells me. “My husband left us to search for some food. My baby is dehydrated, she has diarrhea and fever.” The impact of severe malnutrition on her daughter’s development is apparent in the steep, misshapen slope of her forehead above her large brown eyes. A murky dot marks where traditional healers have attempted a cure, to no avail.

My colleague holds her after we finish speaking. “She's so light,” she whispers to me. “But what a beautiful smile.”

Aid agencies are working feverishly to cope with the surge of displaced people arriving in Maiduguri as government forces liberate areas of Borno State. And while their needs are great, workers are even more concerned for those who haven't made it to the camps.

“What we’ve found to date in many of the recently opened areas has been alarming,” says the IRC’s emergency field director Lani Fortier, “and you can see the high rates of malnutrition here in the capital. But what we’ve yet to find is likely to be much, much worse than anyone anticipated.”

Prior to the violence, Falmata lived a comfortable life on the family farm.

“In our home village, my husband would go to town and bring back a variety of foods. We used to eat potatoes, rice, vegetables, and fish. But now that we have left our village, we haven’t seen my husband for a month because he does small jobs to bring food,” Falmata says.

One of the front lines of the crisis lies to the north: reports from the IRC’s newest field site in Monguno describe an island of desperation at the center of a war zone.

As a result of significant efforts over the past months, the Nigerian Armed Forces have secured the town where more than 60,000 displaced people have erected the barest makeshift shelters - tiny straw huts that stretch for acres across abandoned school grounds - while thousands more live in dire conditions among a host community of more than 200,000 that is scarcely better off after years of conflict, destroyed livelihoods and isolation.

Limited resources are already stretched and people wait for hours to access a handful of wells. A water system is desperately needed to tap into the source and quench the safe haven’s growing thirst. Meanwhile, government forces clash with militant groups within earshot on a regular basis, and as many as 500 newly displaced arrive every week.

Initial assessments illuminate what many fear—alarming rates of malnutrition (32 percent of children under 5) and nonexistent health services. One IRC staff member described his visit to a nearby graveyard: "It was small mound after small mound after small mound.”

Efforts are also underway to reach the hundreds of thousands in the weakening but persistent grasp of Boko Haram. The IRC is coordinating with other aid agencies to provide water and sanitation to Monguno’s growing city of survivors. Nutrition interventions and primary health care programs are also underway to hopefully slow, if not end, the spread of unnecessary small mounds.

Meanwhile, in Maiduguri, we opened a stabilization center in September to treat the most severe and complicated cases of malnutrition. This center represents only the second in Maiduguri – the government has stated that seven will be required to address the scale of this crisis.

The IRC is working with local community health workers to help identify children suffering from malnutrition and admitting them to outpatient feeding therapy programs. We continue to launch more infant and youth feeding programs for parents to learn about how to prepare nutritious meals with the few resources they have. We are also ramping up programs providing counseling and other psychosocial support to women and children struggling to make sense of the vicious attacks they have suffered.

Learn more

Read more about the food crisis in Nigeria.

Get involved