The United States has a long tradition of welcoming refugees who have been forced to flee their homes by conflict and persecution. Help is needed now more than ever, as there are more people uprooted by violence than at any time since World War II.

A June 26 Supreme Court decision to reinstate parts of President Trump’s travel ban, however, threatens to halt these efforts in the name of baseless security concerns.

As a result of the ruling, travelers from six mainly Muslim countries—Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Yemen—who don't have close ties to the U.S. will be temporarily barred. The refugee resettlement program will be suspended for 120 days.

This doesn’t just impact those yet to escape dangerous situations; it impacts vetted refugees already scheduled to come to the United States.

The hardest way to come to the U.S. is as a refugee. Refugees are first registered by the United Nations refugee agency, and then hand-selected by the U.S. government.

Those who are granted entry have an opportunity to rebuild their lives and find new hope.

Below, in their own words, refugees from Vietnam, Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan who were resettled by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in California describe their plights, their dreams and the roads they’ve taken to carve out a new life in America.

1980s: Vietnamese refugees flee by boat

Name: Lieu Thi Dang

Fled: Da Nang, Vietnam

Resides: San Jose, Calif.

Arrived: Nov. 3, 1980

When Saigon fell in 1975, hundreds of thousands of people tried to escape Vietnam in rickety, overloaded boats. Officially, the war had ended, but the shelling and bombing was endless, recalls Lieu Thi Dang, a high-school English teacher from Da Nang. She and many others realized they had no choice but to escape by sea. As their numbers swelled beyond expectations, the United States passed the 1980 Refugee Act, funding the resettlement program that exists today. More than 800,000 Vietnamese refugees, including Lieu, were welcomed to the U.S.

I secured a spot on a private boat bound for Malaysia. It was crammed with 200 others fleeing the mayhem. The journey lasted for four days and five nights and will remain forever etched in my memory. Even now, I remember every detail. Years later on a cruise ship, I could hardly sleep; the gentle rocking took me right back to that cramped boat leaving the only home I had ever known.

When I arrived in Malaysia, I lived in a camp with many others like me. After four months, I was given word that I had been approved for refugee status and offered a safe haven in America. I arrived in San Jose in 1980, and just a week later, I began a job at the International Rescue Committee as an interpreter for the hundreds of other Vietnamese-speaking refugees who resettled here. I also began supporting refugees from Laos and Cambodia, all of us working to make a new life, a new home, in a safe

place.

As the crisis in Southeast Asia subsided, other conflicts arose, and the IRC began to welcome refugees from other parts of the world. In 1987, I became the director of the San Jose office, a job that I was honored to do for 10 years.

I have stayed in touch with relatives in Vietnam, but will probably not return again. I am proud of the good I’ve been able to accomplish and am at peace to enjoy the rest of my life here, as a Californian — as an American.

1990s: Bosnian refugees evade a mass killing

Name: Enes Ceric

Fled: Jajce, Bosnia

Resides: Oakland, Calif.

Arrived: May 24, 1994

The Bosnian War drove 1.3 million people from their homes as ethnic disputes set the Balkans aflame in the 1990s. One of the largest exoduses was from the city of Jajce. In late October 1992, Enes Ceric, then 20 years old, witnessed countless atrocities when Serbian forces surrounded the city.

We didn’t really worry about the war until it was too late. The siege [in my town] broke and it became an urban war — shooting from building to building. After six months, it became clear it was time to go. Ironically, I’d never seen Jajce so peaceful — people hugged and kissed and bid each other farewell, not sure when, if ever, they would see each other again.

My parents went to a family friend’s vacation home in Zenica. I went to Jablanica on the other side of the country where my roommate from college lived. Soon after I began working for the International Rescue Committee as an interpreter.

But after just a few months, it became clear that it wasn’t suitable for a Muslim to remain in a Croat-controlled part of Bosnia. The IRC suggested resettlement, and less than six months after filling out the form, I arrived at San Francisco with just my T-shirt, pants and boots. I met my wife, Lane, in 1997 and we married in 2000. Our son, Ismet (we call him Izzy), was born in 2003. Today, we live in Oakland, just above Lake Merritt in Crocker Highlands.

I went back to Bosnia in 1999 to see my parents for the first time in five years and took Lane. Now we do a trip every two years so Izzy can learn the language and culture. I love visiting, but am even happier to come back to California and hear “welcome home” as we go through customs.

2000s: Iraqi family survives two wars

Name: Hamzah and Rasha Alobaidi

Fled: Baghdad, Iraq

Reside: Oakland, Calif.

Arrived: Jan. 12, 2015

The year 2007 was one of the deadliest times of the Iraqi conflict. Violence escalated and civilian casualties reached record highs. It was then that Hamzah and Rasha Alobaidi decided to begin new lives in Damascus, Syria. Yet three years later, Hamzah and Rasha found themselves once again in the midst of a brutal civil war — forced to flee their adopted home, but now with two young children. Since the beginning of the Syrian conflict, over 4 million refugees like Hamzah and Rasha have been uprooted from their homes by violence, spurring the worst refugee crisis since World War II.

In Syria, we were full of hope that we would be able to start a family in peace. Hamzah had a cell phone repair store and I studied pharmacy at a local university. After I graduated, I began my practice. For a few peaceful years, our lives settled into a rhythm: the monotony of everyday life punctuated by the excitement of children. But in early 2010, just months after welcoming our youngest son into the world, small protests broke out across the country. By April, protests had morphed into an uprising, with violence rippling across Syria.

One night in 2011, we were attacked in our apartment. Hamzah was stabbed and everything of value was stolen. Overnight, the violence we had worked so hard to escape returned to our doorstep, and the life we had struggled to build disappeared. Once again, it was time to go.

We made plans to leave for Turkey, and I would have to leave my mother behind. She was too sick to join us. It was heart-wrenching, but there was no choice. Our children came first.

At this point, we had no illusions of being able to return home to Iraq or to Syria, so we immediately began the paperwork for resettlement in a third country as refugees.

When we found out we were being resettled in the United States, we felt our dreams of having a normal life as a family had come true. We didn’t know anyone in Oakland, but we were determined to do our best. I remember the customs officer at the airport reviewing our documentation. We were nervous, but when he said “welcome home” relief washed over us. We were enrolled in an employment program through the International Rescue Committee that helped Hamzah find a job, and I’ve enrolled in English classes.

Our dreams here are simple: rebuild our careers, raise our children right, one day see our families again. Most of all, we dream of peace.

2000s: Afghans flee terror at home

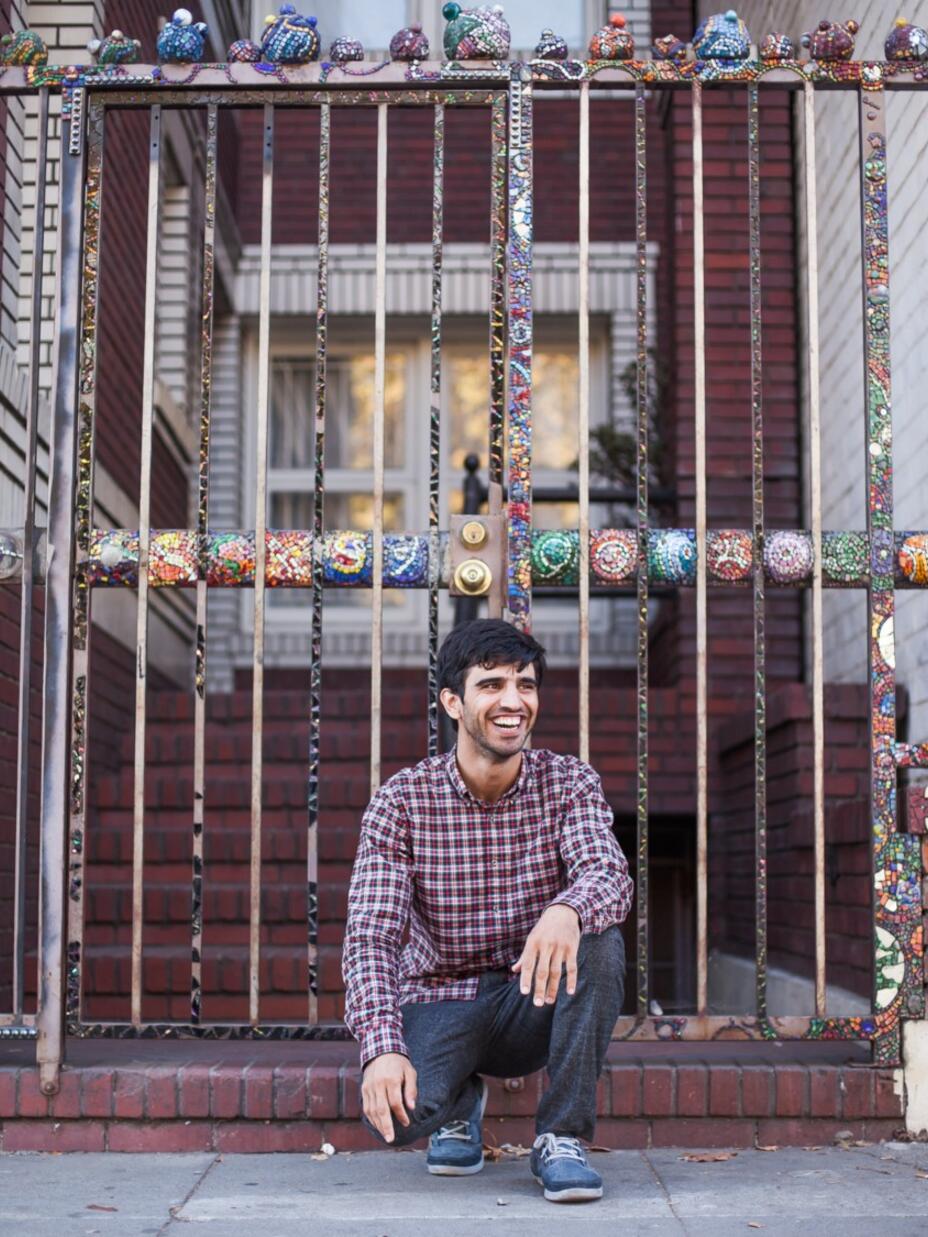

Name: Ajmal Massoumy

Fled: Kabul, Afghanistan

Resides: Oakland, Calif.

Arrived: Oct. 18, 2014

Since the 1970s, Afghanistan has been embroiled in turmoil. Despite progress in building a stable state, a recent Taliban resurgence has created a dangerous environment in many parts of the country. Ajmal Massoumy sought to rebuild his nation, working as an interpreter for the United States Special Forces to help bring peace and stability to local communities. When his full name was broadcast on U.S. radio, Ajmal became a target of the Taliban and was forced to flee for his life. The volatile situation in Afghanistan has uprooted hundreds of thousands like Ajmal, making Afghanistan one of the top ten refugee-producing countries in the world.

It was dangerous work — three of the Special Forces’ interpreters had been killed. I met my 12-person team in Kunduz province; every mission we undertook gave us little chance of coming back alive. We were hit by roadside bombs and shot at from the bushes. Despite this, we saw the positive outcome of our mission in the faces of everyone we helped. We brought peace to the region, training local police and building roads and schools.

I started interpreting for a U.S.-run radio show called Voice of the People. This program sent messages from the U.S. government to the local people, and then broadcast supportive responses from the locals as well. My real name was used and this made me an easy target for the Taliban. I began receiving messages and phone calls with threats against my life. Scared, I turned to my team for help. They told me about the special immigrant visa program and I applied a few months later. I continued working as an interpreter with my team for another year, then went home for six months. When I received word that my application had been approved, I left for the United States.

I found my first job at Chipotle with the help of the International Rescue Committee, got my driver’s license, learned how to file taxes and understand credit. Getting my GED is my next big goal. My life improves every day. I hope to enroll in college soon to study construction engineering, perhaps at the College of Alameda or Berkeley. One day, I know I will return to Afghanistan to rebuild my country.

Refugees fleeing crisis today deserve the same opportunities these new Americans had—no matter what. In 2016, the U.S. admitted over 85,000 refugees, and the IRC helped 13,400 refugees resettle in their new communities. With the travel ban in effect, these numbers will drop at a time when they need to rise—leaving innocent lives in danger or adrift.

A version of this story was first published in the IRC's Uprooted publication on Medium on Dec. 31, 2015.